The Pastor's Prodigal Son

Katy Perry, Rick Warren, Anne Graham Lotz, Franklin Graham, Jonas Brothers, Frank Schaefer, Jessica Simpson. All these names, however disparate they may seem, have something in common: they are all Pastors’ Kids.

When it comes to the Pastors’ Kids, stereotypes abound. First, there is the model child, who lives by the rule book and follows in the footsteps of his minister father. In many churches, this is both an expectation and a stereotype. Perhaps the dominant stereotype of the Pastor's Kid, however, is the prodigal son: the wayward son, the rebel who has strayed from the faith, the backslider who would rather go his own way than live in the shadow of the steeple.

The underlying assumption of this stereotype, however, is that Christians believe that those who have grown closest to the church are the quickest to leave. And as with any stereotype, it's worth taking a closer look to see if any of these perceptions are actually true. After all, those named above have chosen different routes. Some have voluntarily assumed the ministry as their own vocation, while others have completely disassociated themselves from the faith.

Christian, and others have gone through a period of rebellion only to return with a renewed sense of spiritual purpose. So, where does this stereotype of the Pastor’s prodigal son come from? Are those who grow up as children of faith workers really more likely to “disappear” from the church later in life? And is it as big a trend as it is often perceived to be? Barna's latest study put these questions to the test, with surprising results.

THE FAITH OF PASTORS’ KIDS

Certainly, those who have spent their childhood in the front row of the sanctuary are given a unique view of the church, for better or worse. If for the worse, one could understand how this could contribute to a rejection of the faith later in life. Two in five Pastors (40%) say their child, age 15 or older, went through a period in which who significantly doubted their faith.

A fifth of Pastors say this is "very" of their children and another 22% say it is "somewhat" true. This is about the same rate as Millennials today, around 38% of those with a Christian background say they have experienced a similar season of doubt. In other words, Pastors’ Kids are quite normal, just as likely as other children raised in the Church to experience significant spiritual doubts. When broken down into congregation types, the Pastors most likely to agree that their children have faced significant doubt are Pastors who serve white congregations (43%) or traditional churches (51%). In contrast, the Pastors least likely to say this describes their children are Pastors who serve non-white congregations (25%) or non-traditional churches (37%).

Overall, a third of Pastors (33%) say their child is no longer actively involved in church. However, when it comes to the outright rejection of Christian identity, the quips are even fewer. When Pastors were asked if their children no longer considered themselves Christians, only 7% said this was "accurate" of their children. That's less than one in 10. This compares to the national prodigal rate of about 9% among Millennials. The parent-pastors most likely to say this is not entirely accurate of their children are non-mainstream pastors (98%) or Southern Baptist pastors (97%).

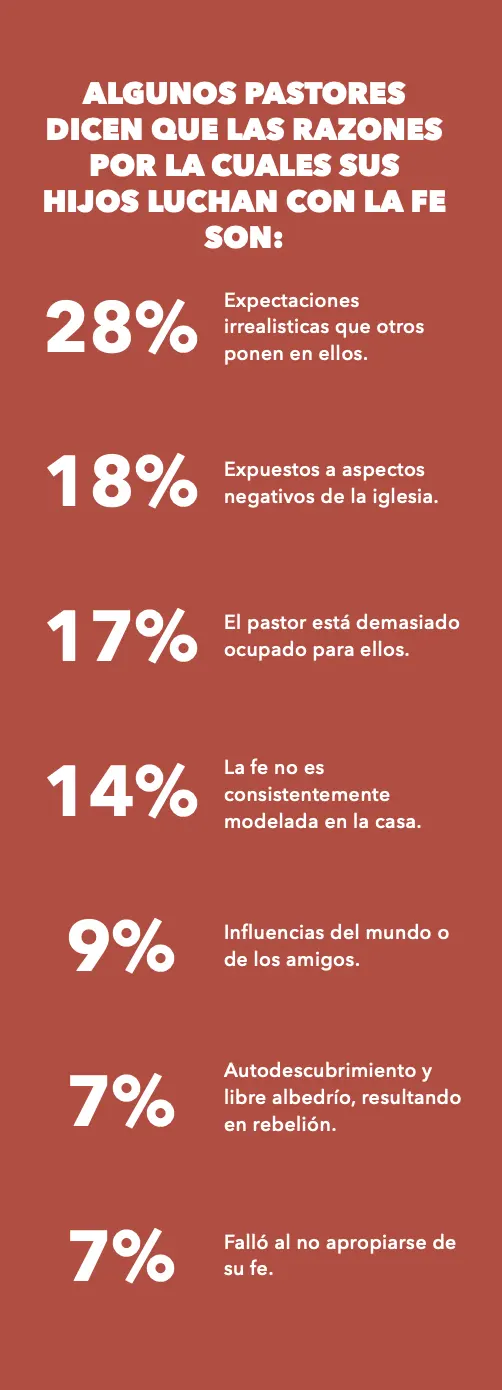

TOP 7 REASONS WHY PASTORS BELIEVE THEIR CHILDREN STRUGGLE WITH FAITH

Yet even if PKs are more spiritually grounded than many realize, it's hard to argue that they don't face distinct social and spiritual challenges. First, PKs are raised in a unique culture of expectations. They share the name of the person in charge and, as such, often live aware that their words, attitudes, and actions are a reflection of the spiritual position of the family. But while their parents may have been called to the ministry, the societal expectations placed on them can cause some Pastors' children to think, "I didn't sign up for this."

The survey results show that Pastors are no strangers to this increased scrutiny of their family. In fact, Pastors (28%) cite their children's unrealistic expectations as the top reason why Pastors’ Kids struggle to develop their own faith. The second reason cited by Pastors (18%) is exposure to negative aspects of the church. But next, the reasons for stunted spiritual growth strike closer to home. Nearly two in 10 (17%) Pastors link their own concern as overly busy parents to their children's frustrated faith. And about a sixth of Pastors attribute their children's prodigal tendencies to a lack of faith consistently modeled in the home (14%). Other reasons given by Pastors include the influence of peers and culture (9%), the free will of the child (7%), and never making the faith their own (6%).

THE PARENTING SUCCESSES AND REGRETS OF PASTORS

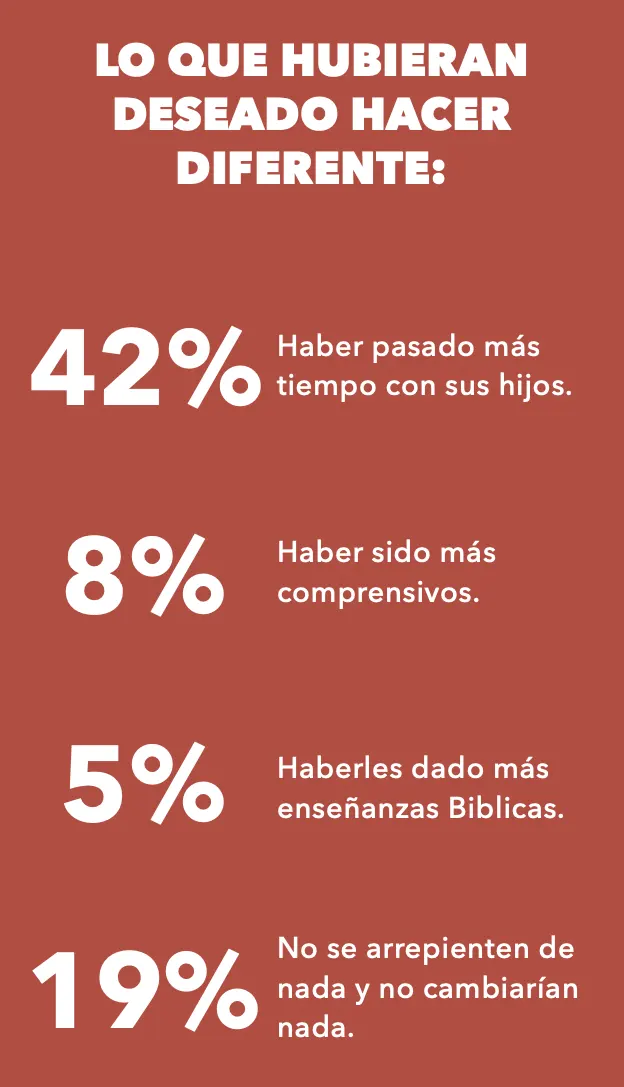

Like all parents, Pastors are only human. And their confessed failures and successes in parenting provide an intriguing study in contrast. In general, the research reveals that Pastors feel they have been successful parents in teaching their children the correct principles to live by, in terms of faith, values, and moral choices. However, when asked about their regrets as parents, Pastors' responses primarily reflect relational shortcomings. When asked what they think they have done best in parenting, Pastors (37%) overwhelmingly responded that they introduced their children to Christ and maintained a Bible-centered home. Only 5% wish they had done better in this area, giving their children more Biblical instruction. Overall, an astonishing 19% say they wouldn't change a thing about their parenting methods, even if they could turn back time.

However, for those who admit parenting regrets, things get a bit more personal. While 21% of Pastors believe they were good parents in terms of support and time with their children, twice that number regret it. In this area: 42% say they wish they had spent more time with their children. Perhaps in reference to the unrealistic expectations that Pastors agree to place on their children, 8% of Pastors also said they wish they had been more understanding of their children.

WHAT DOES THE INVESTIAGTION MEAN?

David Kinnaman, author of You Lost Me, directed the research on pastors’ kids. He comments, “The numbers show that pastors’ kids—at least as reported through the eyes of their parents—are about average when it comes to their struggles with Christianity and with the Church. This is perhaps to be expected, yet also disappointing. The children of pastors are not destined to become prodigals, but more than one out of 14 seem to have left their faith behind. And nearly two- fifths of these church-raised kids go through

a period of significant doubt—we call this the spiritual journey of nomads, those who still call themselves Christians yet are no longer connected to a local church.

A pastor’s kid himself, Kinnaman stresses the importance of pastors and churchgoers maintaining realistic expectations for the children of clergy. “Pastors are feeling the pressure. Their children are living in a moral and spiritual fishbowl; their actions are evaluated by all sides in the church. This constant evaluation is only compounded with the rise of social media and always-on leadership. In fact, it is telling that the most common improvement pastors would make to their parenting, looking back, is to have spent more time with their children. It is a haunting question: Are faith leaders sacrificing their best hours for the sake of other people instead of their own children?”

“On the one hand, a pastor’s family should aspire to be a great example of what a healthy, functioning and grace-filled family looks like. It’s natural to look to our leaders as examples of how we should live.